by Fred Taylor (05/26/09). |

A few years ago I had an elderly lady walk into my antique furniture restoration shop with an unusual request. In a slightly embarrassed manner she told me that she knew this was a professional shop and this was how I made my living, but just this once would I sell her just a little of the “patina” that real pros use. Believe me, if I had had some extra I would have given it to her.

How many times have you heard an appraiser on TV or an auctioneer in person use the term “patina” in describing an antique piece of anything, be it furniture, jewelry clothing, whatever? But if you were able to stop them in mid-sentence could they, in fact, precisely define the word for you? Probably not. As it turns out, the definition of patina is a lot like the definition of pornography. It’s hard to say what it is but you know it when you see it.

There is even discussion about how the word is pronounced. My ancient “American College Dictionary” by Random House places the emphasis on the first syllable so the word is “PAT-ina.” So does the “Columbia Encyclopedia,” Sixth Edition, 2001. In everyday use however, many people—including me—rightly or wrongly, put the emphasis on the second part of the word so it is “pa-TINA.” It doesn’t matter as along as we all know what it means. Or don’t know what it means, as the case may be.

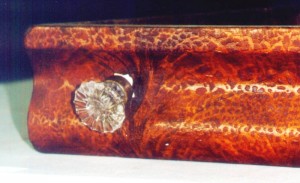

So what does it mean? To some people, the answer is a simple two words: “old dirt.” But that is too simple and not entirely correct. My antique dictionary defines it as a film or encrustation on the surface of an object indicating great age. That’s a good start, but with furniture I think it involves a great deal more than that. The “Encyclopedia of Furniture,” by Joseph Aronson, defines it as “Color and texture of the surface produced by age and wear. In wood furniture the varnish, shellac or oil has a tendency to deepen yet retains transparency; edges wear smooth and sharp outlines are softened.” Now we are getting somewhere.

But that still doesn’t quite cover it. All of those characteristics can be duplicated to some degree by an experienced finisher, so there must be more to it than that. But at least Aronson tried. Many antiques reference books either avoid the subject altogether because it is so hard to handle concisely and accurately, or else they just gloss over it. An example of that treatment can be found in “American Furniture,” by Marvin D. Schwartz, which states that patina is the “Mellow and worn aspect a surface acquires through age; highly desirable quality on most antique furniture.” That steps nicely around it.

John Obbard, in his recent book “Early American Furniture” (Collector Books, 2000), gets a little more precise in saying “Patina is the cumulative effect of age, sunlight, wear and grime on old surfaces of wood and metal …” The “Antiques Roadshow Primer,” by Carol Prisant (Workman, 1999), takes a more humanistic approach. It says patina is “the sheen on a surface caused by long handling …” and that it is “… the accumulation of wax, soil, stains and oils that human hands have left on furniture over the course of many years, have created a smooth film of, well, dirt.” There we have the short of it again—dirt, and we humans are to blame; not sunlight, humidity or atmosphere.

So, by the definitions of the trade, a piece that has patina is dirty, oily, grimy, worn, beat up, faded, rounded and generally disagreeable. By those standards, I have some extremely patinated sneakers. Surely that can’t be the whole thing.

It turns out that patina, whatever it is, has not always been universally desirable. Surely Goddard, Phyfe, Belter and Jellif did not send out their masterpieces all dirty and grimy. They were shiny and clean, new and fresh, and 20 or 30 years ago that was the way much of the antiques trade—including some museum curators—preferred their antiques. And that’s the way many buyers wanted their new old pieces to look. They didn’t want all that dirty old stuff in their new dining room or bedroom, with a crackly old dark finish that could be hiding almost anything, especially the beauty of 200-year-old mahogany. The current emphasis on originality and patina is just that; current. It wasn’t the case 30 years ago and may not be the case 30 years from now.

Perhaps the definition of patina is not as important as we thought it was. Perhaps patina, which, in and of itself, is not always a beautiful thing, judging by the industry definitions, should just be regarded as one more tool of the inquiring collector, used to verify the apparent age of a piece.

Next time you are tempted to discuss the patina of a piece with a dealer or auctioneer, just ask yourself, “Does the piece LOOK, SMELL and FEEL old?” That may be the best definition of all.

Fred Taylor is a Worthologist who specializes in American furniture from the Late Classicism period (1830-1850).

Visit Fred’s website at www.furnituredetective.com. His book “How To Be A Furniture Detective” is now available for $18.95 plus $3 shipping. Send check or money order for $21.95 to Fred Taylor, PO Box 215, Crystal River, FL 34423.

Fred and Gail Taylor’s DVD, “Identification of Older & Antique Furniture,” ($17 + $3 S&H) and a bound compilation of the first 60 columns of “Common Sense Antiques,” by Fred Taylor ($25 + $3 S&H) are also available at the same address.

No comments:

Post a Comment